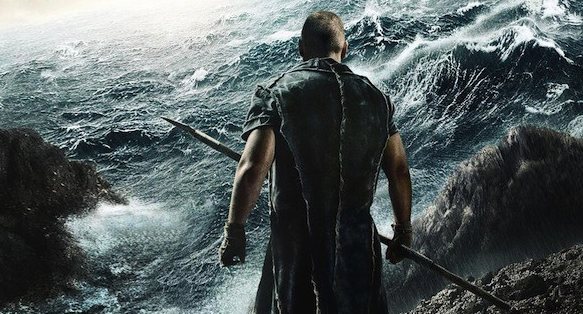

What a lot of twitter, mutter and blog there's been

about "Noah". After all, it's a long way from the fifteenth century Chester Mystery Cycle of plays and even further from the Britten opera in which I was once cast, improbably, as the Voice of God. Church leaders have been sounding off about extra-biblical

Nephilim, flawed angelology and Big Bang pastiches about Creation. People taking

liberties with the historical Tubal-Cain, mangy, lizard-eating stowaway as he is portrayed - Ray

Winstone’s South London gangster accent and all - and all kinds of incestuously

lascivious unspoken backstories about Noah's sons' wives - or lack of them.

The Ark looks like a gigantic floating wardrobe, as improbably buoyant as this Seine river boat, into which the pachyderms and reptiles lumber, swarm and slither in their multitudes, settling into their prearranged spaces as if by orchestral direction, obediently sleeping, anesthetized with a smoke-wreathed censer, as birds swirl satisfyingly inwards.

The Ark looks like a gigantic floating wardrobe, as improbably buoyant as this Seine river boat, into which the pachyderms and reptiles lumber, swarm and slither in their multitudes, settling into their prearranged spaces as if by orchestral direction, obediently sleeping, anesthetized with a smoke-wreathed censer, as birds swirl satisfyingly inwards.

Aronofsky's Noah seems to have

become disturbed, apparently by the depravity of the rest of his species, so

much so that he obsesses on the idea that humanity should not survive. This isn't the first time he's gotten away with stellar portrayals of tortured souls - 'The Wrestler' (2010) almost brought Mickey Rourke back from the dead. In this new incarnation, Noah believes that the

Creator must be using his family just to save the animal kingdom and then

mankind will simply fade into extinction – a rather second-rate Day Six attempt

at the best of the best. If his son's wife has a baby girl, Noah announces that

he will take that life to prevent the human race from continuing. Later, with

Noah's knife raised over twin daughters, suddenly the myths get busted and

there are two of them, Noah and Abraham, conflicted and close to losing reason. No wonder he turned to drink.

It’s fictional. It’s a movie. References to Gnostic thinking, whispers of Kabbala notwithstanding, it’s just Hollywood and it will no more bring people closer to God than the next incarnation of X-men. The Icelandic

landscapes are satisfyingly primitive and the special effects remarkable. We

briefly wonder where all the wood is going to come from in a barren volcanic

wasteland until the miraculous growth of a forest, the “fountains of the great

deep” explosively funnel water upwards as the deluge pours down, but the best

characterization is a wily old Anthony Hopkins, suitably wizened by great age,

as Noah’s grandfather Methuselah, with magical powers, a fondness for berries

and a nice touch in fertility. Six (or maybe even seven) out of ten.